Assessing how much capital to raise requires an understanding of the company’s forecast financial performance, including those initiatives that funding will be used to accelerate.

To do this, you will need to prepare a financial forecast model that includes a cash flow. If you don’t already have one, see our dedicated guide to creating a growth-stage financial model.

Ensure that you include in your plan what you intend to invest the money in, for example, new hires, acquisitions, marketing, investment in technology, new premises. If cash does not dip into the negative then you may not need to raise funding at all.

With these assumptions included, the cash flow will illustrate the quantum of cash required, equal to the lowest negative balance.

Add an appropriate quantum of headroom to this figure to calculate the total funding requirement.

While this will vary for each business and your risk appetite, one approach is to assume that the business should be able to survive for 3 months in the instance that all income ceases. This would give you a window of time to establish new income or raise funding.

Strip out all turnover and income and calculate the company’s monthly outgoings. Multiply this figure by three months to calculate an estimate for cash headroom.

You may choose to increase this figure if:

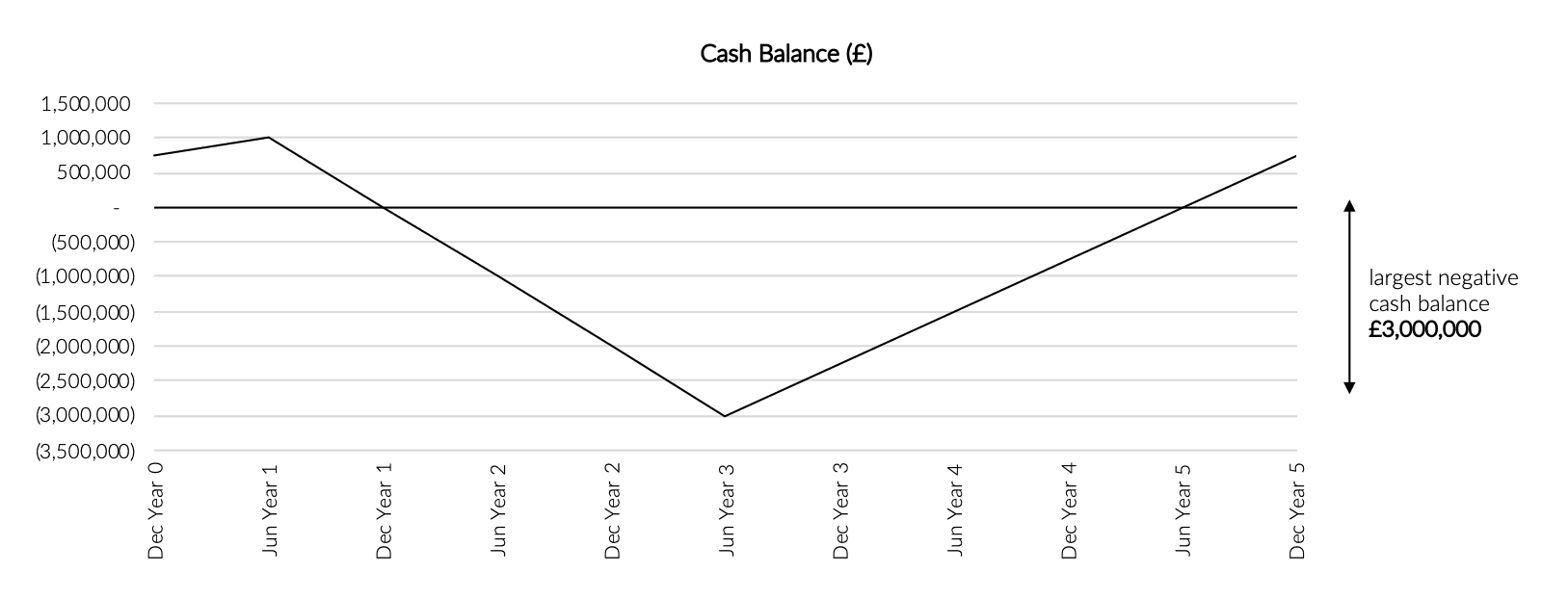

The business in this example is profitable and cash generative; however, it intends to invest in operating expenditure and capital expenditure in order to accelerate growth. For a period of time, this investment in expenditure results in cash depletion, before the return on this investment is realised and the company becomes cash generative again.

Funding is required to enable the business to invest in additional expenditure and accelerate turnover growth.

The business is expected to run out of cash in August and reach a cash low point of minus £3,000,000 the following February.

The monthly cash depletion rate, assuming no income, is approximately £200,000 per month. An appropriate level of cash headroom is considered to be £600,000.

The total cash requirement is therefore:

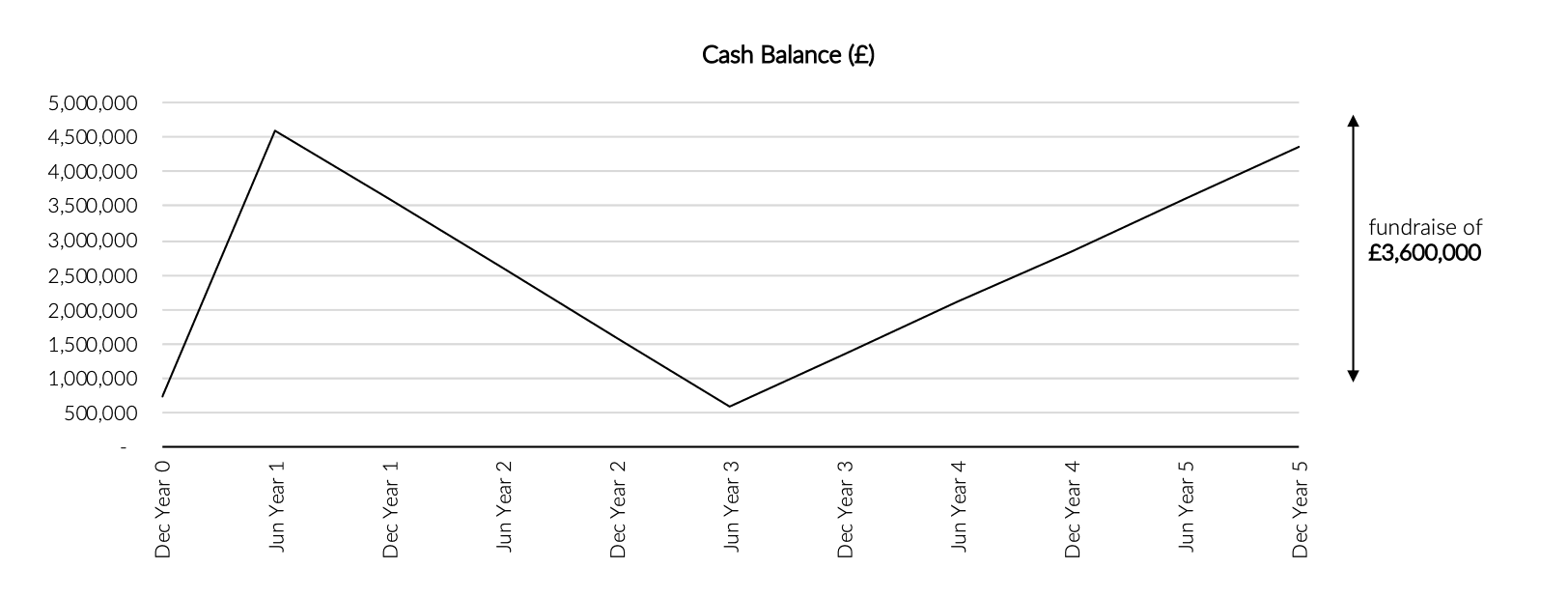

Assuming a successful raise in June, the cash flow now looks like this:

In the example above, the fundraise of £3,600,000 is sufficient to deliver the five year business plan without further capital.

With an investment horizon of 3 to 5 years being typical of the industry, most investors want to see a business plan of 3 to 5 years that is fully funded, i.e. does not require further capital, beyond the initial investment, to achieve.

It may be that there are incremental growth initiatives that arise during the course of the investment, which can provide additional investment opportunities for the investor.

For particularly high growth businesses, some investors may be comfortable with forecast cash headroom of at least two years, which is the period before which a further funding round will be required.

The caveat to raising 100% of the funding required over a forecast 3 to 5 year period is that, for a growing business, you are raising at the point when the value of the business is likely to be at its lowest, and thus experience greater equity dilution as a result. In certain circumstances, investors are willing to tranche their investments to better meet the cash flow profile of the business. For example, a restaurant business may raise investment for each individual restaurant opening. This approach may bring some valuation advantages but does entail greater uncertainty, higher fees and repetition in the process.

When doing a seed round, investors will usually expect you to come up with a proposed price for the round, at least as a starting point.

It is very difficult to price early stage companies, as it involves a significant amount of judgement and guesswork. The core valuation principles that apply to large, listed companies, stock markets and even private equity backed companies, are difficult to apply as they rely heavily on multiples of profit and do not take into account the rapid growth rate of many small companies.

Ultimately, the theorems underpinning corporate valuation are a representation of the collective view held by investors of an appropriate risk-adjusted return. Therefore, once you have a starting point for discussion with investors, you will soon find out whether they agree that it represents an attractive risk-adjusted return through uptake and / or negotiation. The objective being to settle on a price that all parties are comfortable with.

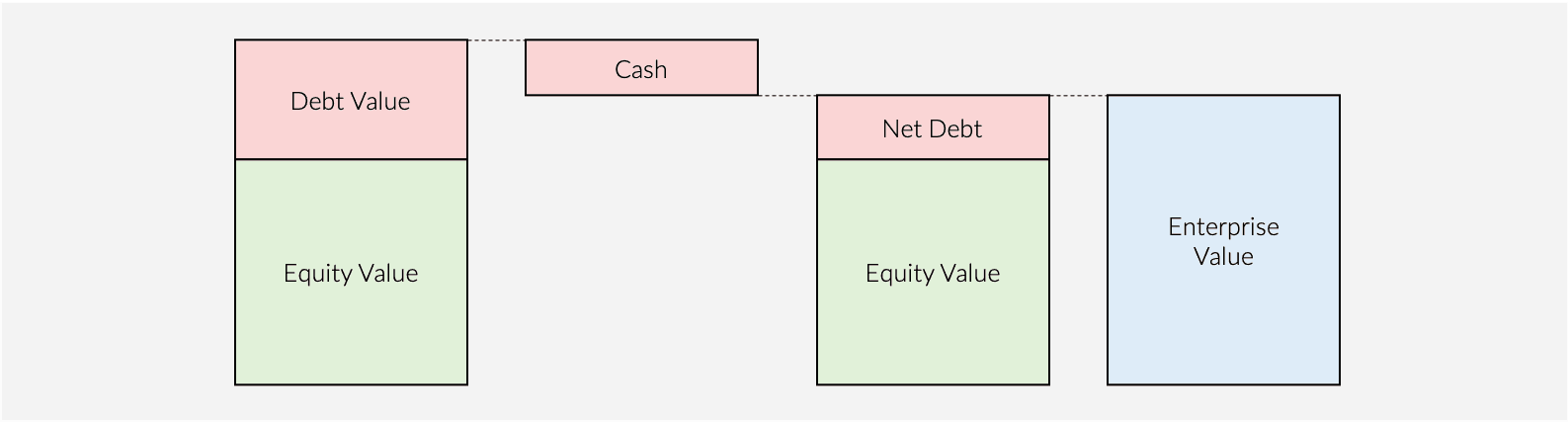

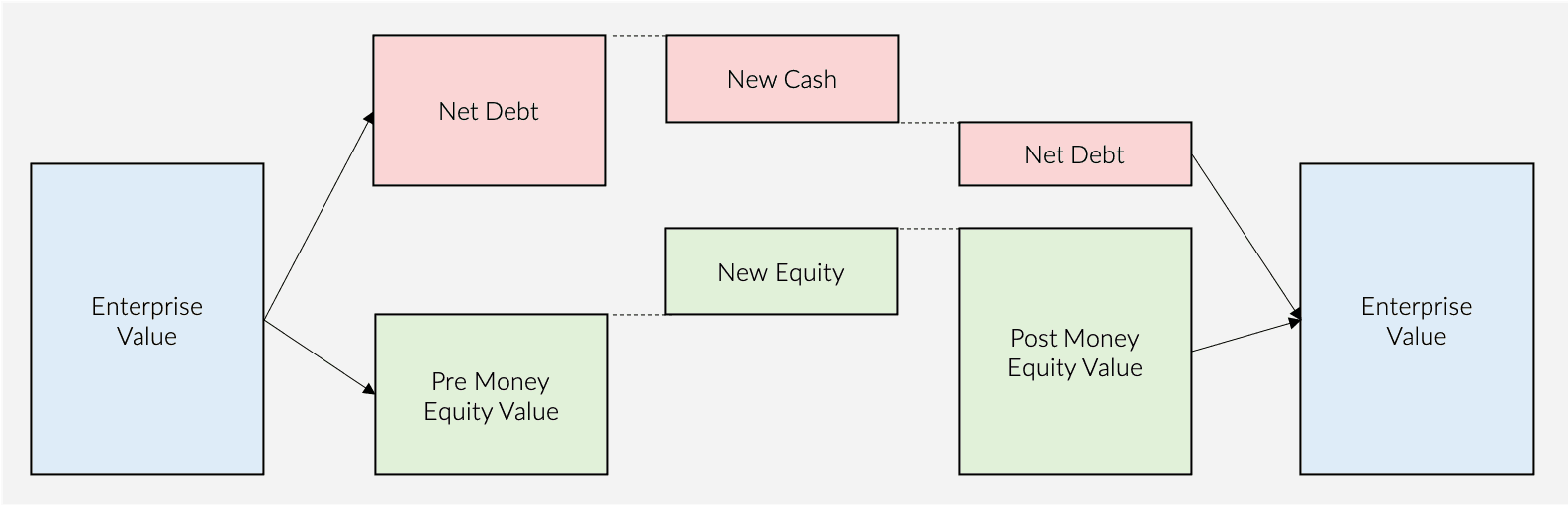

The value of a business is called the “Enterprise Value” or “EV”. It is a common misconception that valuation increases when you raise equity – this is incorrect. It is not possible to alter the value of a company through changing the way in which it is financed – only through utilising that investment to generate more money, can value be created.

The EV of a business therefore remains the same before and after raising money. The terms pre-money equity value and post-money equity value refer to a portion of the EV only.

The EV represents the total value of claims that each stakeholder has on the business. Stakeholders comprise:

Debtholders rank in priority to shareholders.

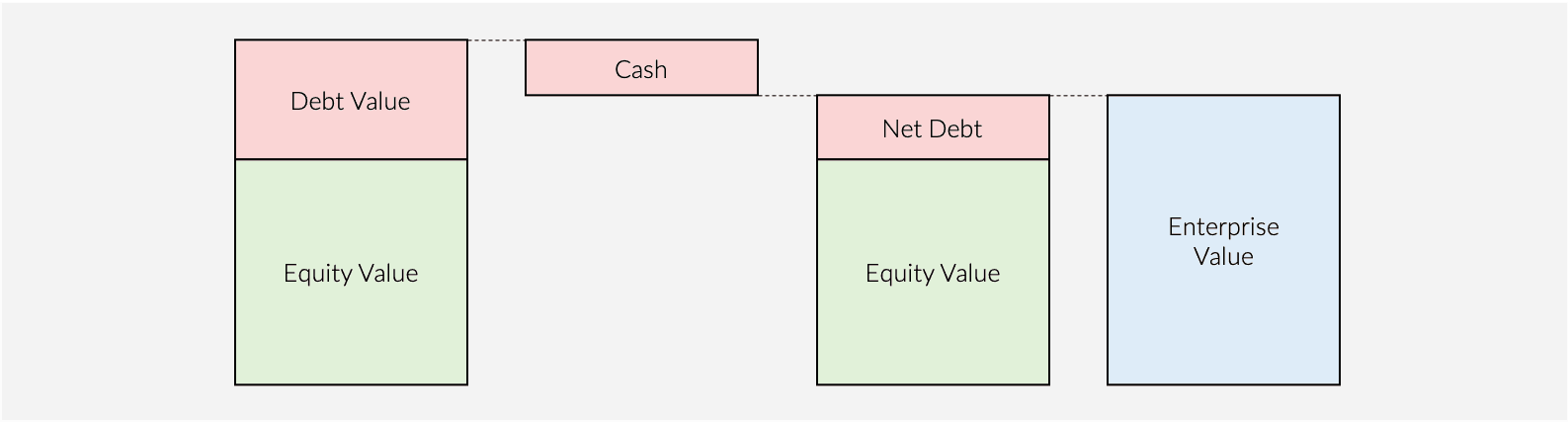

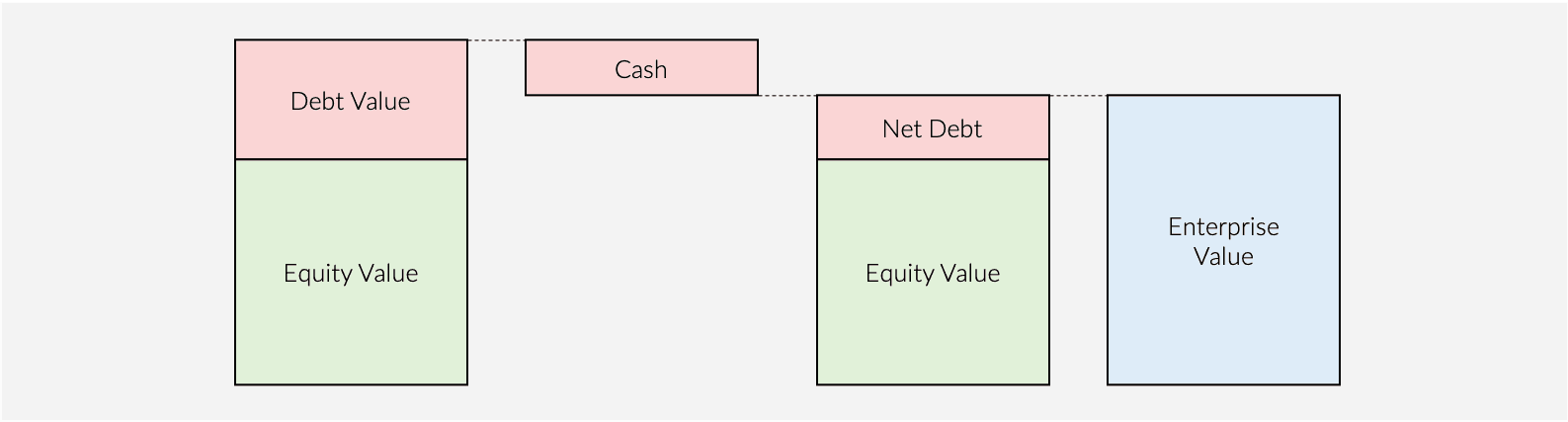

EV is essentially the value owned by the debtholders (“Debt Value”) plus the value owned by the shareholders (“Equity Value”), minus the cash sitting on the balance sheet. If there is cash on the balance sheet, then this can theoretically be used to pay back some of the debtholders. Debt minus cash is referred to as Net Debt and therefore:

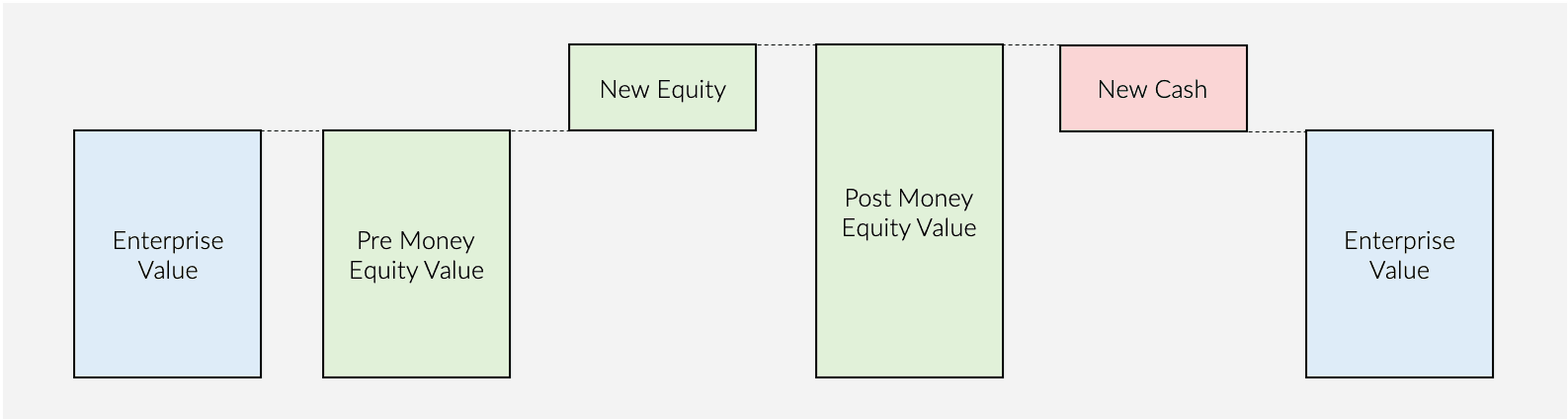

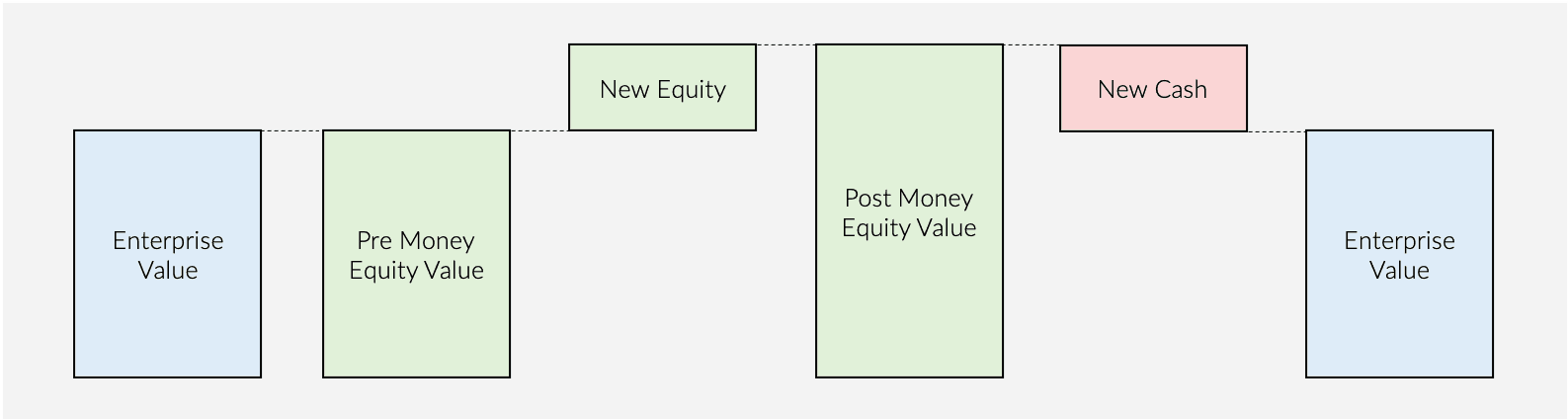

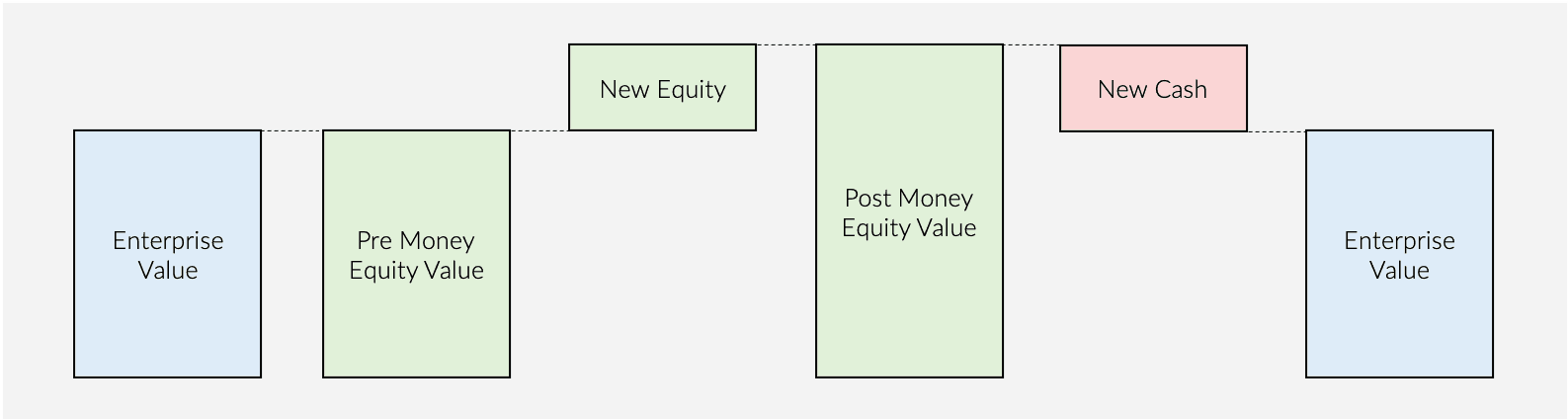

If no one has lent you any money (and debt includes shareholder loans), then your fundraise will look like this:

The newly issued shares represent new equity value, and thus the post-money equity value is higher than the pre-money equity value.

The new cash on the balance sheet is effectively negative net debt and is deducted to reach the post-investment EV – which will always equal the pre-investment EV.

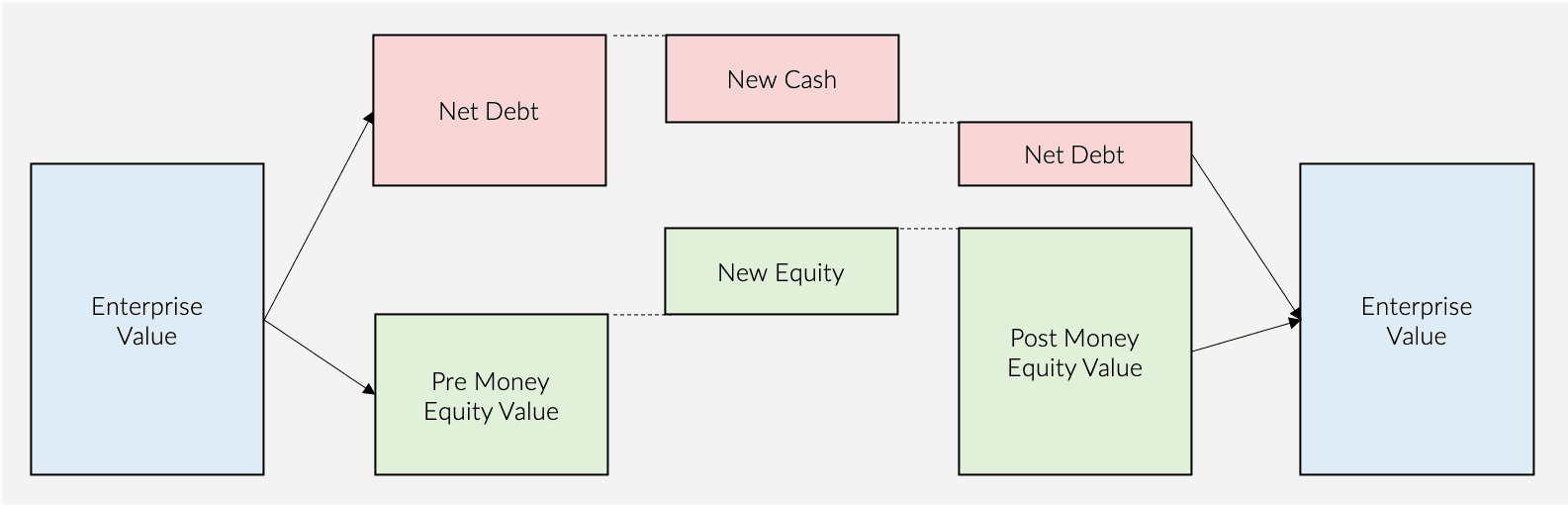

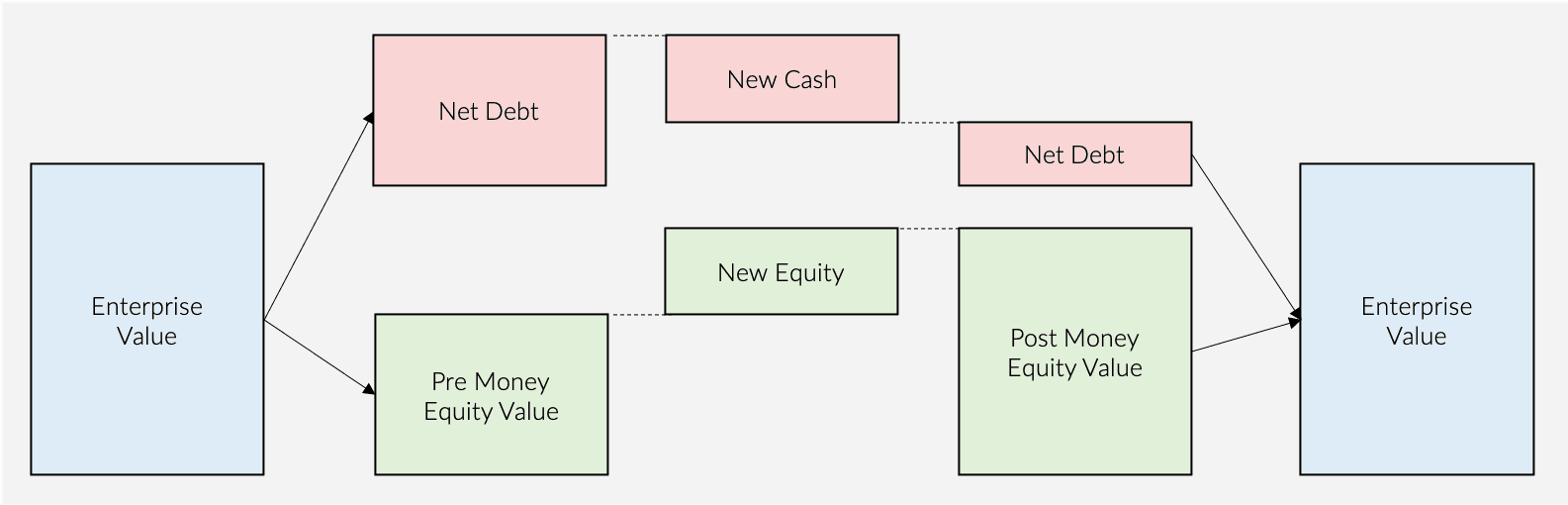

If you have debt or shareholder loans on your balance sheet, then your fundraise will look like this:

The newly issued shares increase the equity value but the new cash reduces net debt and thus EV remains the same.

It is important when pitching to investors to be clear which metric is being used when talking about price or valuation. For seed rounds, it is common to refer to the pre and post-money equity value while making investors aware of any existing debt.

A typical proposal would read as follows:

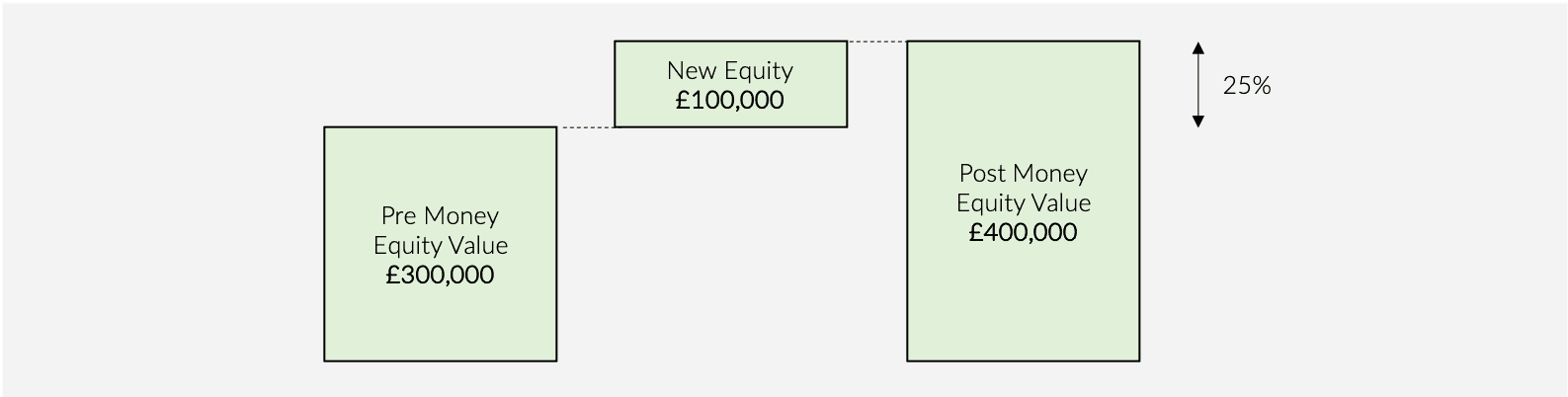

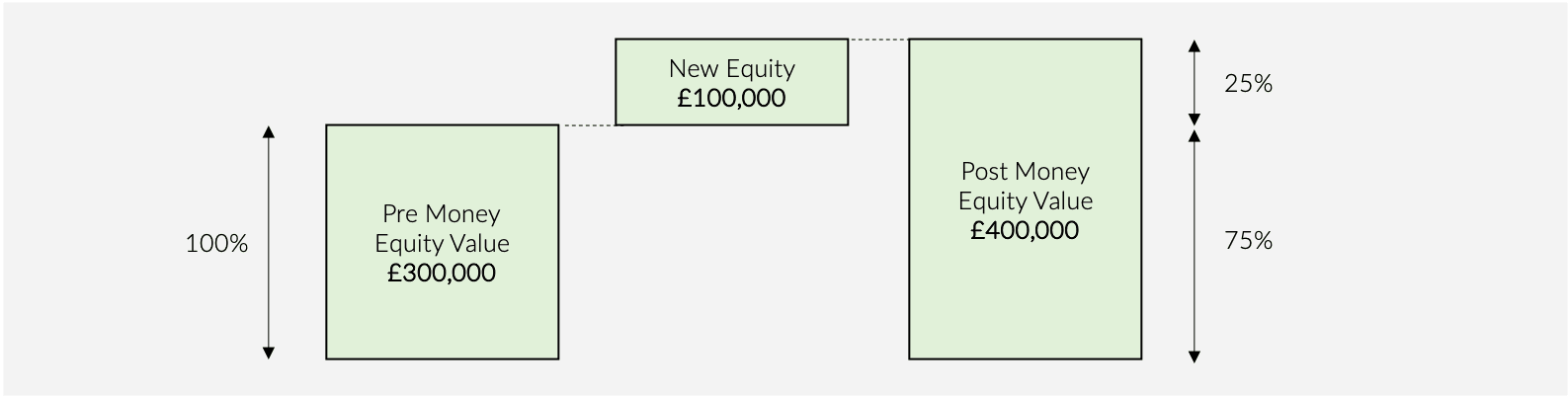

“We are seeking investment of £100,000 in return for 25% of the equity in the company”

In this example, the implied post-money equity value is:

i.e. £100,000 / 25% = £400,000

The pre-money equity value is:

i.e. £400,000 - £100,000 = £300,000

We focus here on the methods of valuation that are used in practice for early stage companies doing a seed round.

Gather the valuation data of companies that have recently raised funding and that you consider to be similar to your own. Specifically, you want to find out the equity percentage acquired and the amount invested.

This will give you the information you need to calculate the post-money equity value for each transaction, unless it is directly disclosed. If the equity stake is not disclosed, you may be able to find this in their latest annual return on Companies House. There are also databases that are dedicated to collating this data, such as Crunchbase.

For each comparable, do some research into their key KPIs, for example: turnover, rate of growth, profit, number of employees, technology, IP, number of sites / offices / locations. This will give you a sense for how these businesses compare to yours and what may be an appropriate valuation for your business.

For later stage companies, the comparable transactions method is formalised such that multiples of Turnover and EBITDA are established. These multiples are not applied to equity value metrics as they will not be comparable and they must take into account the entire capital structure of the company, i.e. equity value and debt value. The EV of each comparable transaction can be calculated through EV = post-money equity value + net debt. You can find their net debt on their latest filed balance sheet but note that net debt must be the post-transaction net debt and thus deduct the new cash raised. Their Turnover and EBITDA can also be sourced from their latest filings at Companies House.

EV / Turnover and EV / EBITDA multiples can then be produced for each comparable transaction. You can apply the average multiple to your own Turnover or EBITDA to establish an estimate of EV for your business.

Using your forecast financial plan, you can estimate the potential exit value for your company and calculate the expected return to investors.

Most investors assess their returns on a money multiple basis, that is:

Expectations vary significantly according to the sector and individual investment preferences, but are underpinned by the logic that investors will seek a return that is commensurate with the level of risk they are taking on. A very high risk strategy that requires significant investment and entails rapid growth may require a return of 10-20x. A low risk strategy that requires modest investment and growth may require a return of 3-4x. Returns are typically measured over a 3-5 year period.

The first step is to estimate the exit value: how much might someone pay to acquire your business in 3-5 years’ time? If your business is expected to become profitable, you can apply a multiple to your forecast profit in 3-5 years’ time to calculate the Enterprise Value (the price that an acquirer would pay for the business). As discussed above, multiples for comparable transactions can be sourced to provide a justifiable estimate for the multiple applied to your business.

To calculate the return to the investor, first calculate the Exit Equity Value using your forecast net debt:

Their proceeds on exit are calculated as:

Note that this assumes that no further funding was required to deliver the 3-5 year plan – if you do intend to raise further funding, it would be prudent to assume that the investor’s equity stake is diluted by some degree, say, 50%.

If this number is too low, for example, 3.5x when you consider your plan is high-growth and high-risk, then by adjusting the Investor Equity % upwards, you can increase this to what you feel is appropriate.

Now you have the amount that they will invest and the equity stake they will hold, and so:

The pre-money equity value is:

Now that you have an estimate of how much you want to raise and the equity stake you will offer in return, you can calculate the share price. Note that the share price of the company will be the same before the transaction and after the transaction – it follows the same logic as the Enterprise Value – each share does not become worth more purely through raising investment.

And as a final error-check, the share price should also be:

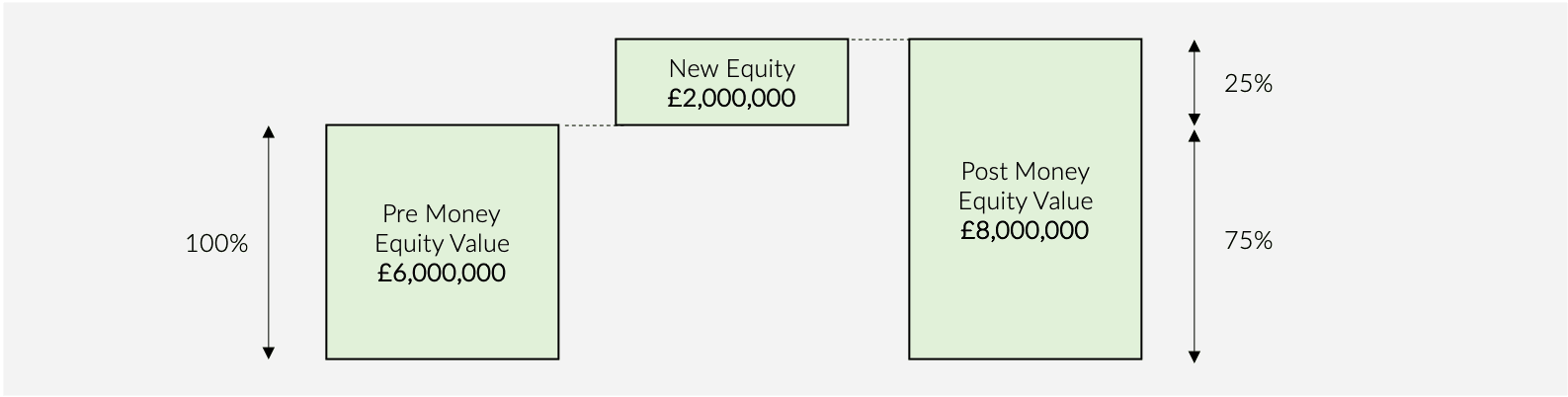

If you are the sole shareholder, this is simple, as following the round you will hold whatever is left of the equity – if new shares representing 25% were issued, then your existing shares will now represent 75% of the equity.

If you have multiple shareholders, it is best to model this through a cap table, but you can also calculate this individually as follows:

Setting out the pre and post shareholder structure

This should be done through a cap table – see our guide on creating a cap table for a seed round.

It is not essential to make a proposal to venture capital firms with regards to the price of the round – most investors run their own valuation and returns models in considering their offers; however, it is important to understand how valuation works so that you can have a meaningful discussion with potential investors, and ultimately judge and respond to offers.

If you are raising from a group of investors, then you would typically negotiate and agree the valuation with the lead investor in the first instance, which may then be tweaked depending on how discussions go with the other investors. If you have no lead investor, you may find it is simply more practical to provide a proposal on valuation than to rely on individual proposals from investors. Certain corporate-backed and strategic investment funds also rely more heavily on businesses conducting their own valuation analyses, compared to traditional venture capital funds.

It is very difficult to price small, high growth companies, as it involves a significant amount of judgement and guesswork. The core valuation principles that apply to large, listed companies, stock markets and even private equity backed companies, are difficult to apply as they rely heavily on multiples of profit and do not take into account the rapid growth rate of many small companies.

Ultimately, the theorems underpinning corporate valuation are a representation of the collective view held by investors of an appropriate risk-adjusted return. Therefore, once you have a starting point for discussion with investors, you will soon find out whether they agree that it represents an attractive risk-adjusted return through uptake and / or negotiation. The objective being to settle on a price that all parties are comfortable with and represents a fair return for both existing shareholders and new investors.

The value of a business is called the “Enterprise Value” or “EV”. It is a common misconception that valuation increases when you raise equity – this is incorrect. It is not possible to alter the value of a company through changing the way in which it is financed – only through utilising that investment to generate more money, can value be created.

As a side note - it’s worth being aware that this misconception, surprisingly, has also made its way into the venture capital funds themselves. If investors refer to the value increasing upon investment, they are referring to the equity value alone, and not the value of the business.

The EV (the value) of a business remains the same before and after raising money. The terms pre-money equity value and post-money equity value refer to a portion of the EV only.

The EV represents the total value of claims that each stakeholder has on the business. Stakeholders comprise:

Debtholders rank in priority to shareholders.

EV is essentially the value owned by the debtholders (“Debt Value”) plus the value owned by the shareholders (“Equity Value”), minus the cash sitting on the balance sheet. If there is cash on the balance sheet, then this can theoretically be used to pay back some of the debtholders. Debt minus cash is referred to as Net Debt and therefore:

If the business has no debt and no cash (and debt includes shareholder loans), then the fundraise will look like this:

The newly issued shares represent new equity value, and thus the post-money equity value is higher than the pre-money equity value.

The new cash on the balance sheet is effectively negative net debt and is deducted to reach the post-investment EV – which will always equal the pre-investment EV.

If you have debt or shareholder loans on your balance sheet, that exceed your cash balance, then your fundraise will look like this:

The newly issued shares increase the equity value but the new cash reduces net debt and thus EV remains the same.

It is important when pitching to investors to be clear which metric is being used when talking about price or valuation. For venture rounds, it is common to refer to the pre and post-money equity value while making investors aware of any existing debt and cash balances.

A typical proposal would read as follows:

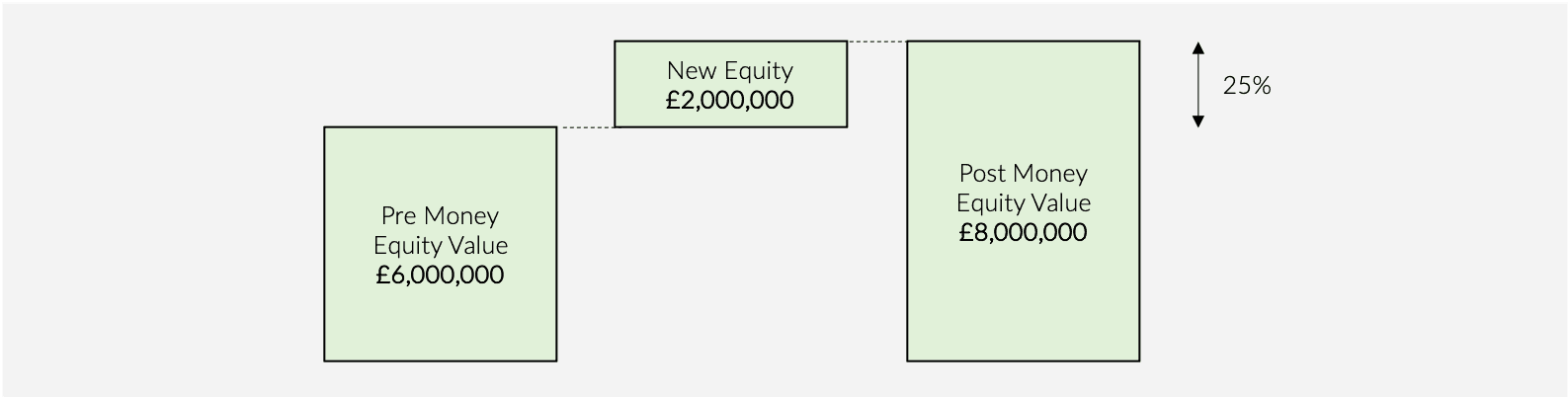

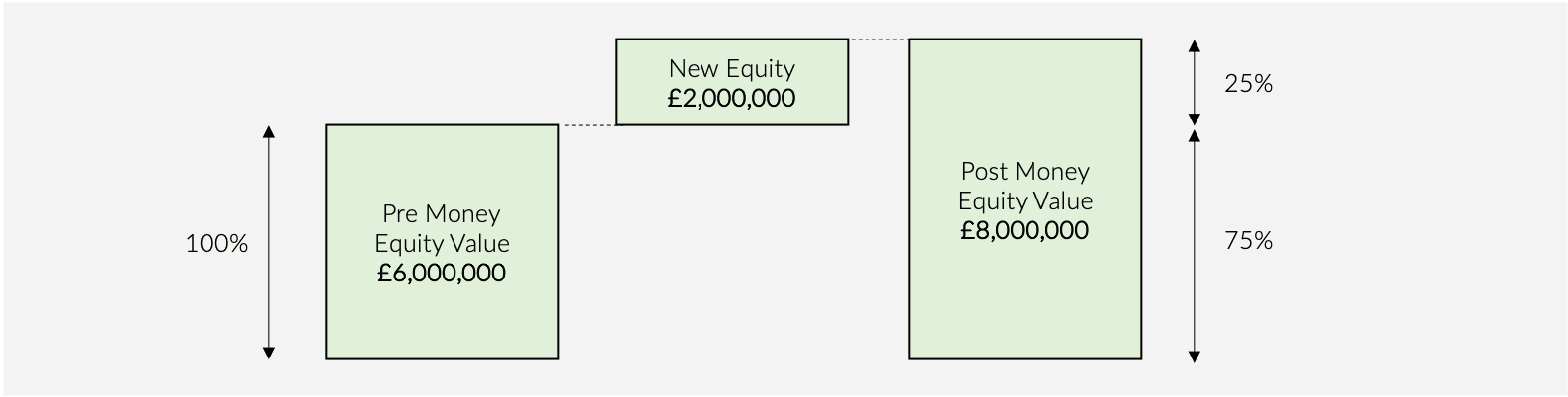

“We are seeking investment of £2,000,000 in return for 25% of the equity in the company”

In this example, the implied post-money equity value is:

i.e. £2,000,000 / 25% = £8,000,000

The pre-money equity value is:

i.e. £8,000,000 - £2,000,000 = £6,000,000

In the same way that investments work in other industries, such as in the commodities, corporate bonds and property markets, the fundamental principle of corporate valuation is that the price paid should be such that, when the investor exits their investment, they receive an appropriate return on their money for the risk that they have taken on.

In order to grow and raise further funds themselves, venture capital funds wish to demonstrate to their own investors that not only will they generate an appropriate return for the risk, but they will generate above-average returns (something investment bankers call “alpha”).

Valuation is therefore important – if too high a price is paid across too many investments, the fund will not generate a sufficient return.

Venture capital funds typically measure the risk adjusted return in two ways:

The former is the most commonly used when assessing the valuation of potential investee companies, so to keep this simple, we will focus here.

To generate an appropriate risk adjusted return across the fund, venture capital firms must take into account the failure rate of small companies. When assessing new investment opportunities, it is not uncommon for funds to target potential returns of 10-20x their initial investment.

A 10x return on a £2m investment requires £20m to be returned to the fund on exit – if that occurs over a 5 year period, it represents an IRR of almost 60%. This is why venture capital is a more expensive form of financing when compared to bank loans or mezzanine financing, but it is also significantly riskier for the fund, as it is highly likely some or many of their investments will underperform or even fail.

It is the strategy of almost all venture capital funds, to generate this return through increasing the value of the business, not through attempting to under-pay for a company. A fair valuation on entry and exit distils the investment thesis down to the drivers of equity value over the investment horizon. So how do you estimate fair value on entry? One such method is known as the multiple method.

The multiple method relies on the assumption that companies operating within similar industries and with similar characteristics, are worth the same, or a similar, multiple of turnover and / or earnings.

The greater the likelihood of higher future earnings and therefore higher future returns, and the more certain those earnings are, the higher the multiple will be. For example, businesses and industries that are growing very quickly will typically command higher multiples of their current earnings. Businesses with good revenue visibility, for example those with long term customer contracts or recurring revenue, will also attract higher multiples because future earnings are more certain.

For example, a technology business with recurring revenues, good visibility of forecast income that is growing rapidly may be valued at 2.0x turnover and 12.0x EBITDA (Earnings before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation). A similar business that is growing more quickly could be valued at 2.5x turnover and 15.0x EBITDA.

To gather applicable multiples to apply to your company’s turnover and EBITDA (if profitable), you can look at listed companies and comparable transactions. Here we will focus on comparable transactions as these are most relevant to venture rounds. The aim here is to find out what other investors and buyers have paid for businesses that are similar to your own.

The first step is market research – who has invested in your industry and who has been acquired? There are a few good sources of this information, including Crunchbase. You could also check the websites of private equity or venture capital funds to see if they have acquired or invested in anything in your industry, and search the web for press releases relating to the deals. Try to find relatively recent investments (in the last 5 years).

For each acquisition, wherever the data is available (as it often is not), note down:

For each fundraise, note down:

For the company’s financials, you may need to do a search of Companies House to review the accounts filed at the time.

Next calculate approximate Turnover and EBITDA multiples for each transaction. For acquisitions, this will be:

For investments, first estimate the post money equity value:

Then calculate the pre money equity value. In a business with minimal or no debt and cash, this is a close proxy for the Enterprise Value:

To be theoretically accurate, you should calculate the EV using the net debt of each company; however, this is arguably an onerously detailed approach as you are looking for a guide, not an exact metric. If using the pre money equity value as a proxy for EV then:

You will now have a set of Turnover and EBITDA multiples (though most likely fewer of the latter if some are loss-making companies). Take the average or a weighted average, if certain companies are more similar to yours than others, and apply these multiples to your own Turnover and EBITDA:

If your business is loss making, then only the Turnover approach will apply. If your business is profitable, and generating what you consider to be a steady-state margin, then the EBITDA approach should take precedence over Turnover, as investors place greater importance on the generation of profit than turnover.

With an estimate of your company’s EV, you can calculate the pre-money equity value:

Then the equity stake you would offer to investors is:

Using your forecast financial plan, you can estimate the potential exit value for your company and calculate the expected return to investors, ensuring this is likely to be sufficiently high for them to be interested.

Returns are typically measured on a 3-5 year investment horizon. In this example we will assumed 5 years:

Apply the average multiple used above to your Turnover and / or EBITDA in year 5 to calculate an estimate of the exit EV (i.e. the price that someone might pay for the business at that time). Note that you can use a different multiple on entry and exit as the metrics of the business may have changed. A lower growth rate would imply a lower multiple, but if the business is larger and more established, this could be justifiably left as is. Value that is not reflected in income or earnings could justify a higher multiple, for example, brand value or IP.

Calculate the proceeds to all shareholders:

Then investor proceeds on exit are calculated as:

Finally, calculate the investor’s expected return:

If the return looks too low relative to the riskiness of the business plan, then you can adjust the following:

At the end of this exercise, you should have a broad estimate of the equity stake to offer to, or accept from, investors in return for their investment, and relevant market data to back this up.

Note that the share price of the company will be the same before the transaction and after the transaction – it follows the same logic as the Enterprise Value – each share does not become worth more purely through raising investment.

And as a final error-check, the share price should also be:

If you are the sole shareholder, this is simple, as following the round you will hold whatever is left of the equity – if new shares representing 25% were issued, then your existing shares will now represent 75% of the equity.

If you have multiple shareholders, it is best to model this through a cap table, but you can also calculate this individually as follows:

Setting out the pre and post shareholder structure

This should be done through a cap table. If you don’t have a cap table set up, you can use our dedicated venture-stage cap table resource [LINK].

Understanding how business valuation works is critical in negotiating with potential investors, not only in assessing the level of equity dilution to accept, but also in understanding how to interpret offers, in particular those that comprise a combination of investment instruments, such as loan notes or preferred equity.

It is not essential to put forward a valuation proposal when approaching investors – as they will run their own valuation and returns models internally; however, investors may ask the question, and some companies prefer to set the boundaries of their expectations, and provide relevant data to inform the investor’s analysis.

On the whole, it is difficult to value small and medium sized, high growth companies, and as a result, investors take a variety of approaches and applying common sense. Ultimately, the theorems underpinning corporate valuation are a representation of the collective view held by investors of an appropriate risk-adjusted return. The objective being to settle on a price that all parties are comfortable with and represents a fair return for both existing shareholders and new investors.

The value of a business is called the “Enterprise Value” or “EV”. It is a common misconception that valuation increases when you raise equity – this is incorrect. It is not possible to alter the value of a company through changing the way in which it is financed – only through utilising that investment to generate more money, can value be created.

The EV of a business remains the same before and after raising money and represents the total value of claims that each stakeholder has on the business. Stakeholders comprise:

EV is essentially the value owned by the debtholders (“Debt Value”) plus the value owned by the shareholders (“Equity Value”), minus the cash sitting on the balance sheet. If there is cash on the balance sheet, then this can theoretically be used to pay back some of the debtholders. Debt minus cash is referred to as Net Debt and therefore:

If, prior to the transaction, the business has no debt and no cash, then the EV will equal the pre-money equity value and the fundraise will look like this:

The newly issued shares represent new equity value, and thus the post-money equity value is higher than the pre-money equity value.

The new cash on the balance sheet is effectively negative net debt and is deducted to reach the post-investment EV – which will always equal the pre-investment EV.

If the business has debt or shareholder loans on the balance sheet, that exceed the cash balance, then the fundraise will be as follows:

The newly issued shares increase the equity value but the new cash reduces net debt and thus EV remains the same.

Investors are seeking to generate an appropriate return for the level of risk they are taking on: the risk adjusted return. This is usually measured in two ways:

The former is the most commonly used when assessing the valuation of potential investee companies, so to keep this simple, we will focus here.

It is the strategy of almost all investment funds to generate this return through increasing the value of the business, not through attempting to under-pay for a company. A fair valuation on entry and exit distils the investment thesis down to the drivers of equity value over the investment horizon. So how do you estimate fair value on entry? One such method is known as the multiple method.

The multiple method relies on the assumption that companies operating within similar industries and with similar characteristics, are worth the same, or a similar, multiple of earnings and / or turnover.

The most commonly used metric for earnings is EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation), because it provides a good representation for the profits a business generates regardless of how it is financed and is also a good proxy for cash. EBITDA should represent the ongoing earnings of the business and should exclude any exceptional or one off items. Therefore:

A multiple of turnover may be used as a further sense-check, or if profitability is artificially low owing to investment in expenditure and rapid growth:

The greater the likelihood of higher future earnings and therefore higher future returns, and the more certain those earnings are, the higher the multiple will be. For example, businesses and industries that are growing very quickly will typically command higher multiples of their current earnings. Businesses with good revenue visibility, for example those with long term customer contracts or recurring revenue, will also attract higher multiples because future earnings are more certain.

For example, a technology business with recurring revenues, good visibility of forecast income that is growing rapidly may be valued at 2.0x turnover and 12.0x EBITDA (Earnings before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation). A similar business that is growing more quickly could be valued at 2.5x turnover and 15.0x EBITDA.

To gather applicable multiples to apply to your company’s turnover and EBITDA (if profitable), you can look at publicly traded companies and comparable transactions.

We have built a simple model to enable you to capture both of these methodologies.

Public companies helpfully summarise the views of a large group of shareholders – their views on the value of the company set the stock price. By looking for listed companies that are similar to your own (similar industry, similar revenue profile etc. albeit they may be significantly larger) you can calculate the multiples that they are trading at and apply these to your own business.

Step 1 – Collate a list of relevant companies and calculate their EV

Make a list of companies that operate in your sector, or do something similar to your company.

Look up the Equity Value of each, also known as the Market Capitalisation (or “Market Cap”, which is the share price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding). There are numerous sources for the Market Cap of individual companies, for example, Yahoo Finance.

You now need to add the Net Debt (Debt Value minus Cash) to calculate the EV of each company. This can be found on the company’s latest balance sheet. For UK companies, their Annual Report or Half Year Report, for US companies, their latest 10K or 10Q, available in the Investor Relations section of their websites, or if using Yahoo Finance, go to “Financials” and select Balance Sheet. Note down Short Term Debt, Long Term Debt and Cash.

And finally, EV:

Step 2 – Calculate each comparable company’s multiples

To calculate the multiples that each company is trading at, you will need their Turnover and EBITDA.

While EV represents the value of a company today, turnover and earnings are generated over a period of time. Therefore, you can calculate multiples for various time periods.

An TTM (“Trailing Twelve Months”, or LTM “Last Twelve Months”) multiple takes EV and divides it by the TTM of turnover or earnings. An NTM (“Next Twelve Months”) multiple takes EV and divides it by the NTM of turnover or earnings, per the company's forecasts as estimated by brokers. NTM multiples can also be called one-year forward multiples. Investors like certainty and are most likely to use TTM multiples given they are based on actual turnover and/or earnings that are “in the bag”. To calculate a TTM multiple, you need the company’s TTM Turnover and TTM EBITDA.

These figures can be calculated from a company’s financial accounts; however, Yahoo Finance also calculates TTM figures, which may be easier and quicker to use. Go to “Financials” and “Income Statement”. If EBITDA is not reported, this can be calculated from EBIT (or Operating Profit) and adding back Depreciation and Amortisation (which can be found in the cash flow statement).

For each comparable, you now have an estimate for the EV of the company and the TTM Turnover and TTM EBITDA. Divide the EV by each of these to get your TTM multiples.

Investors will calculate these multiples for a number of publicly traded companies and take the median, not the average, so that it is not skewed by the exceptional circumstances affecting any one particular company multiple.

Step 3 – Apply the median multiples to your company’s financials

Multiply the median Turnover multiple with your TTM Turnover, and the median EBITDA multiple to your TTM EBITDA, to provide two estimates of your business’s EV.

This method follows the same logic as publicly traded multiples – the aim is to find out what other investors and buyers have paid for similar businesses to yours.

Step 1 – Collate a list of relevant transactions

The first step is market research – who has bought who in your industry?

There are a number of platforms that aggregate this information, though most require membership (such as MergerMarket, CapitalIQ, Beauhurst and Crunchbase). The information they use is often drawn from public sources, so if you are not a member of one of these platforms, you can simply Google for specific transactions and source the relevant press releases.

Transactions should be relatively recent (past 3 years ideally) and there should not have been any significant market shifts between the transaction and today.

Step 2 – Source the Price Paid, Turnover and EBITDA of the target company at the time of the transaction

Once you have a list of deals, for each deal, you will need to try and find out:

The first place to look is the press release for the transaction – if the price paid hasn’t been made public then you won't be able to use that deal. If it has, but there are no financials quoted for the company, then you’ll need to search for their financial statements to obtain TTM Turnover and TTM EBITDA at the time of the acquisition. See above for how to find these figures for public companies. If the acquired company is private and based in the UK, then their historic statements can be downloaded from Companies House.

For each comparable transaction, you now have an estimate for the EV of the company and the TTM Turnover and TTM EBITDA. Divide the EV by each of these to get your TTM multiples.

Step 3 – Apply the median multiples to your company’s financials

Multiply the median Turnover multiple with your TTM Turnover, and the median EBITDA multiple to your TTM EBITDA, to provide two estimates of your business’s EV.

With an estimate of your company’s EV, you can calculate the pre-money equity value:

Then the equity stake you would issue to the new investor is:

Using your forecast financial plan, you can estimate the potential exit value for your company and calculate the expected return to investors, ensuring this is likely to be sufficiently high for them to be interested.

Returns are typically measured on a 3-5 year investment horizon. In this example we will assumed 5 years:

Apply the average multiple used above to your Turnover and / or EBITDA in year 5 to calculate an estimate of the exit EV (i.e. the price that someone might pay for the business at that time). Note that you can use a different multiple on entry and exit as the metrics of the business may have changed. A lower growth rate would imply a lower multiple, but if the business is larger and more established, this could equal the entry multiple. Value that is not reflected in income or earnings could justify a higher multiple, for example, brand value or IP, that has been created over the course of the business plan.

Calculate the proceeds to all shareholders:

Then investor proceeds on exit are calculated as:

Finally, calculate the investor’s expected return:

If the return looks too low relative to the riskiness of the business plan, then you can adjust the following:

At the end of this exercise, you should have a broad estimate of the equity stake to offer to, or accept from, investors in return for their investment, and relevant market data to back this up.

Note that the share price of the company will be the same before the transaction and after the transaction – it follows the same logic as the Enterprise Value – each share does not become worth more purely through raising investment.

And as a final error-check, the share price should also be:

If you are the sole shareholder, this is simple, as following the round you will hold whatever is left of the equity – if new shares representing 25% were issued, then your existing shares will now represent 75% of the equity.

If you have multiple shareholders, it is best to model this through a cap table, but you can also calculate this individually as follows:

This should be done through a cap table. If you don’t have a cap table set up, you can use our dedicated venture-stage cap table resource [LINK].

Early stage investments often rely disproportionately on future customer acquisition relative to historic trading. For this reason, it is a good idea to prepare a customer pipeline analysis before putting together the more detailed financial model. It is also something you may choose to summarise in the investor presentation.

A customer pipeline analysis is a table that sets out the current and new customer assumptions that underpin the company’s forecasted turnover. It does not have to align exactly with forecast turnover, but can be used to illustrate to investors how achievable the forecasts are and to what extent they are underpinned by secured customers and ongoing discussions.

While each business will have a different pipeline, the common objective is to demonstrate realistic and backable assumptions and strong traction.

This is most relevant to B2B businesses. If you are a B2C business with a significant number of users / customers, we recommend including user growth and price per user assumptions within the forecast financial model.

The extent of variability between businesses means that it is not practical to start from a template – so instead we’ll walk you through how to create one from scratch, to align with your business.

Step 1 – Segment and Describe

In Excel, create a list of all of your current customers and potential customers with whom you are in discussions. In the adjacent column, write a few words describing what the business does or the sector they operate in – investors will be interested to know who your customers are.

Segment customers into categories that represent how progressed they are. We recommend between 2 and 5 stages, for example:

Or:

Sort the list by category so that the most advanced customers are at the top of the list.

Step 2 – Apply Probability Weighting

Allocate a probability of success / conversion to each category, to reflect the reality that not all discussions will result in a sale, for example:

Step 3 – Input Turnover Assumptions

The pipeline should ideally cover a period of two years – the first being the current fiscal year and the second being a forecast year. If you have good visibility beyond that, then you can extend it, but most businesses do not.

Create a column for “Actual or Expected Start Date”

Create a column for each month and input actual Turnover figures for all existing / secured customers up to the present month.

Then, for each customer:

Step 4 – Aggregate

Create a “Total” column at the end of year one and year two, that sums up the monthly Turnover to give total Turnover for that fiscal year by customer.

Create an adjacent column entitled “Proportion of Total Turnover” and calculate the percentage contribution of each customer to the years’ total Turnover. This is an important metric for investors as it illustrates any customer concentration.

A common mistake is to assume that Cash is equal to Turnover.

For example, a subscription business that charges an upfront annual fee of £12,000 in month one, should not input £12,000 as Turnover in month one.

While there are accountancy nuances, the principle that investors follow is that Turnover should be recognised in the month to which the product or services relate.

The subscription business provides access to their product for the entire year, and therefore Turnover is spread evenly over this period. Turnover in month 1 is in fact £1,000, not £12,000.

Getting Turnover right is important to investors as it helps them to assess the growth rate of the business and margin. It is particularly relevant in the definition and calculation of Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR). If you are unsure of how this applies to your business, one of our consultants would be happy to help – you can view our consultancy services via your dashboard.

The first external fundraising that a company undertakes.

Friends, family, members of your professional network, business angels, possibly SEIS / EIS funds or seed funds, startup accelerators, crowdfunding platforms.

While most seed rounds are between £250k - £750k, it is possible to raise more depending on valuation, your willingness to dilute, the funding requirement of the company, industry in which the company operates and growth potential.

Ordinary equity, i.e. shares in your company.

Once you have prepared your investor materials, a significant portion of the raise is spent meeting with and pitching to potential investors to build up a pool of committed capital. During this process, investors will ask questions that form part of their due diligence. Once all of the funding is committed, the legal documentation is prepared and the round can be completed.

Depending on how long it takes to secure commitments, it can be very quick – as short as a month, but will usually take 3-4 months from start to finish, so it’s good to start the process comfortably in advance of when the cash is needed.

A pipeline analysis is a good way to demonstrate likelihood and certainty of future income and forecasts, and can therefore be helpful to include a summary of in the investor presentation. The pipeline should bring credibility to the near time financial forecasts presented in the model, and it may also help you to set what your future forecasts should be.

It can be seen as a more detailed and specific description of how and why the business will grow. It is most relevant to B2B businesses and harder to apply to B2C businesses. For the latter category, there are other ways to support the company’s forecasts, for example, a restaurant businesses would instead demonstrate the pipeline of potential new restaurant sites.

A customer pipeline analysis is a table that sets out the current and new customer assumptions that underpin the company’s forecasted turnover. It does not have to align exactly with forecast turnover, but can be used to illustrate to investors how achievable the forecasts are and to what extent they are underpinned by secured customers and ongoing discussions.

While each business will have a different pipeline, the common objective is to demonstrate realistic and backable assumptions and strong traction.

This is most relevant to B2B businesses. If you are a B2C business with a significant number of users / customers, we recommend including user growth and price per user assumptions within the forecast financial model.

The extent of variability between businesses means that it is not practical to start from a template – so instead we’ll walk you through how to create one from scratch, to align with your business.

Step 1 – Segment and Describe

In Excel, create a list of all of your current customers and potential customers with whom you are in discussions. In the adjacent column, write a few words describing what the business does or the sector they operate in – investors will be interested to know who your customers are.

Segment customers into categories that represent how progressed they are. We recommend between 2 and 5 stages, for example:

Or:

Sort the list by category so that the most advanced customers are at the top of the list.

Step 2 – Apply Probability Weighting

Allocate a probability of success / conversion to each category, to reflect the reality that not all discussions will result in a sale, for example:

Step 3 – Input Turnover Assumptions

The pipeline should ideally cover a period of two years – the first being the current fiscal year and the second being a forecast year. If you have good visibility beyond that, then you can extend it.

Create a column for “Actual or Expected Start Date”

Then, for each customer:

Step 4 – Aggregate

Create a “Total” column at the end of year one and year two, that sums up the monthly Turnover to give total Turnover for that fiscal year by customer.

Create an adjacent column entitled “Proportion of Total Turnover” and calculate the percentage contribution of each customer to the years’ total Turnover. This is an important metric for investors as it illustrates any customer concentration.

Venture capital investments may be defined in a number of ways, but when we use the term “venture” we are referring to what is usually a company’s first or subsequent institutional investment, i.e. funding sourced from a professional fund. A venture round may follow a seed round, undertaken with individuals or dedicated seed-stage funds.

Venture capital is usually associated with high growth, often technology oriented companies.

One or a group of venture capital funds, EIS funds, VCT funds or other early stage funds.

Typically between £1m and £10m but there are no hard rules and this will depend on the specifics and attractiveness of the investment opportunity.

Equity that may be ordinary equity or preferred equity, i.e. shares with preferential legal and commercial rights attached. Venture investors ordinarily hold minority stakes and rarely take controlling stakes in a business.

Initial preparation of investor materials is important to ensure the investment opportunity is adequately represented. Initial meetings will be held with institutional funds and investors where they will assess the opportunity. If these discussions progress, then you will normally be issued a term sheet setting out the terms on which the investor is willing to invest. If multiple investors are taking part in the round, then usually a lead investor is secured first who then leads the negotiation on behalf of the other investors.

Once a term sheet is agreed, due diligence will commence and the legal documentation will be negotiated and agreed.

Provided that due diligence is satisfactory, the transaction will then complete.

From preparation of investor materials to completion, the process can take as little as a few months but six months is more typical. The greatest variation occurs in the stages before a term sheet is issued and agreed, when initial conversations with potential investors are being held.

These terms primarily relate to the stage and profile of the business raising investment.

Venture capital is usually deployed into highly scalable, high growth and high risk companies. Many venture capital backed companies are technology oriented to enable this rapid growth to occur, but some occupy other sectors.

The traditional venture capital investment strategy involves making highly selective investments into a number of high growth companies. The associated higher risk entails a higher failure rate, and thus each portfolio company must be expected to contribute a sufficiently high return to compensate and enable the fund to generate a return.

Growth capital is usually deployed into growing companies that are not necessarily as high growth or high risk as venture capital backed companies. As a result, growth capital is often invested into non-tech sectors, such as professional services. The lower growth profile entails lower risk, and thus a higher number of portfolio companies are expected to deliver a return. Return expectations for growth capital investors tend to be lower than those of venture capital investors.

There are a number of grey areas too. Companies may be suitable for both venture and growth capital, and the route taken may depend on the risk appetite of the board – does the team want to pursue a higher risk, high growth strategy, or a lower risk, lower growth strategy?

Companies that initially raise venture capital, for example in a Series A, may go on to mature and become suitable for growth capital, as their growth curve flattens. Companies that initially raise growth capital may experience a significant uptick in growth and subsequently seek a subsequent investment with venture-oriented investors to their shareholder structure.

While the majority of funds typically describe themselves as “venture” or “growth”, there are also some that play in the space between. The VCTs (Venture Capital Trusts) are often seen as somewhere in between – some take a more venture-leaning approach while others are more growth oriented.

Investors in a seed round will not be expecting an all-singing, all-dancing financial model; however, they will expect to see basic figures to help them to understand:

Regardless of what your investors may or may not expect, as a founder it’s useful to have an idea of how the business is expected to grow and how much funding it requires to do so.

Our basic seed round template is quick and easy to complete and tailor. Alternatively, it can be used as a guide as to what investors will expect to see and thus what may need to be added or amended in your existing model.

Input your company name and the current fiscal year end – these inputs will change the column headings throughout the model.

The P&L starts with Turnover and allows for 3 different categories, each with their own Gross Profit so that you can model different margins, if desired. Add or remove categories as necessary to suit your business. You may also wish to add sections above Turnover that include the key components of Turnover, again, tailored to your business; for example, price and volume, number of users and income per user.

Forecast Turnover utilises a year on year growth rate assumption, i.e. how much Turnover grows from January one year to the January of the following year, thus taking into account any seasonality. For an annual growth rate of 30%, input 30% in every month of the relevant year. For most small businesses, growth rate steadily declines, so it may start at 150% in January and fall to 50% in December of a particular year.

The model provides for five categories of overhead costs. Add or remove rows here as appropriate and label according to your business.

Input the relevant tax rate – this may be zero if the company is loss making.

There is nothing to add here as it is automatically generated from other inputs, unless you want to model additional balance sheet items.

To keep the model simple and easy to apply to different businesses, it excludes: intangible assets such as goodwill, prepaid expenses, accrued revenue, deferred revenue or accrued expenses. If you wish to model these, add these as extra lines in the Balance Sheet and Cash Flow.

Note that the Balance Sheet won’t balance until all of the inputs throughout the model have been populated. Once this has been done, if there is a consistent error in the balance, for example, 100 every month, then the starting shareholders equity balance must be amended by that amount in the Balance Sheet Schedules tab.

The cash flow statement is generated automatically from other inputs so there is nothing to add on this tab, with the exception of the closing cash balance at the start of the period. The data for the cash flow graph is included in this tab.

The model allows for up to two lines of debt, which could be overdrafts, term loans and/or shareholder loans. If you have more than two, copy and paste one of the schedules and add a line into the Balance Sheet and Cash Flow. Rename each line of debt accordingly, input the applicable interest rates, current balances and any anticipated drawdowns or repayments.

Input the current tangible assets balance and any forecast capital expenditure – these are the expenses that you capitalise as opposed to expense in the P&L, for example, purchase of assets. The model calculates Capital Expenditure as a percentage of Turnover to provide a sense check.

The model assumes a depreciation policy of 20% of capital expenditure per annum, or 1.7% per month – this can be amended as appropriate and is intended to be an approximation, as it is applied to the monthly opening fixed asset balance.

Input the trade debtor balance for each month of the current year, i.e. the balance at the end of each month representing income that has been invoiced but not yet received in cash. The model uses the current year data to calculate average debtor days, i.e. the number of days it takes for customers to pay, which may inform the assumption that you use for debtor days in the forecast years.

Complete the inventory / stock and trade creditor schedules in the same way.

Input the starting shareholders equity balance and any anticipated equity investment or dividends.

Here are a few house-keeping checks:

A balancing balance sheet

Make sure your balance sheet balances, i.e. that total assets equal total liabilities plus shareholders equity. If it doesn’t balance, the model will show you what the delta is each month. If this delta is consistent every month, there is likely an error in the starting shareholders equity balance. If the delta increases each month, then it is likely that one of the items included in the balance sheet does not have a corresponding entry in the cash flow or vice versa (which may occur if you have added extra line items).

Cash headroom

A review of the cash graph will give you a sense for whether the model approximates your anticipated cash flow and for how much funding you need to raise.

Turnover and margin trends

Check that the trends in turnover and margins look sensible, realistic and there are no unusual movements. There is an annual summary to the right of each statement to provide the macro view. Ensure that the figures fairly reflect what you intend to achieve as a business and can be relied upon by investors.

Growth capital is raised by established, growing companies that utilise it to accelerate their growth. These companies issue new equity to private investment funds, which may be alongside or instead of other forms of financing such as bank loans.

Unlike the traditional venture model, in which multiple rounds of financing are raised, growth capital may be the first external equity injection into a business, and may also be the last, depending on the cash needs of the business.

It is also common for existing shareholders to realise a return on their own investment to date and sell a portion of their shares to the new investor, depending on how established the business is. This is sometimes referred to as “cash out”.

It is usual, but not always the case, that the new investor holds a minority equity stake, in contrast to the more traditional private equity model in which the investor holds a majority stake and controls the business. As a result, the investment represents the formation of a partnership between the old and new shareholders, and the management team.

Institutional investment funds are the primary source of growth capital for businesses. These funds may be structured in a variety of ways, for example:

Co-investment is less common for growth-stage businesses, as the entire round can usually be sourced from a single fund; however, occasionally funds do invest alongside one another. It is relatively rare for more than two funds to participate.

Typically, between £1m and £20m depending on the specifics of the business and opportunity.

In its simplest form, growth capital is structured as equity, i.e. new shares, in the company. The equity will ordinarily be structured as a new class of share to allow for the fact that investors often require certain “special” rights that other shareholders do not.

In practise, growth capital investments can be structured across a spectrum of instruments that vary in their level of commercial risk and return:

Each investment can be structured as one or a combination of the above, to provide the right balance of risk and return to the new shareholders and existing shareholders.

Initial preparation of investor materials is important to ensure the investment opportunity is adequately represented. Initial meetings will be held with institutional funds and investors where they will assess the opportunity. If these discussions progress, then you will normally be issued a term sheet setting out the terms on which the investor is willing to invest.

Around this time, the investor will prepare and present a paper to their internal investment committee. There may be one or multiple sittings of investment committee throughout the transaction.

Once a term sheet is agreed, due diligence will commence and the legal documentation will be negotiated and agreed. Provided that due diligence is satisfactory and agreement has been reached on the legal documentation, the transaction will then complete.

This can vary considerably based on how long it takes for the business to prepare investor materials, how initial discussions with investors go and whether any issues arise during due diligence. Assuming no significant roadblocks in the above, a process typically takes 6 months from start to finish.